Iran's Oil Sector Returns to Form

Oil and geopolitics crossed paths repeatedly throughout the 20th century. And perhaps nowhere were the political effects of their intersection more pronounced than in Iran. For nearly five decades, the Anglo-Persian Oil Co., later renamed Anglo-Iranian Oil Co., the forebear of what would eventually become British Petroleum, enjoyed near total control over Iran’s oil sector. When Iran nationalized the sector in 1951, the United States and United Kingdom responded by overthrowing its architect, Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, just two years later. Those events heavily influenced the 1979 Iranian Revolution, a foundational element of which was resource nationalism.

And now it appears that BP is returning to its roots. During the week of May 2, the head of Iran’s national oil company announced that BP will soon open an office in Tehran. Meanwhile, the country is opening up its energy sector and considering admitting foreign oil companies to set up joint ventures and operate oil fields there for the first time since 1979.

But Iran faces new challenges. To revive his country’s economy after years of sanctions, President Hassan Rouhani is driving an initiative to reinvigorate the oil sector.

Iran’s Paradox: Nationalism and Pragmatism

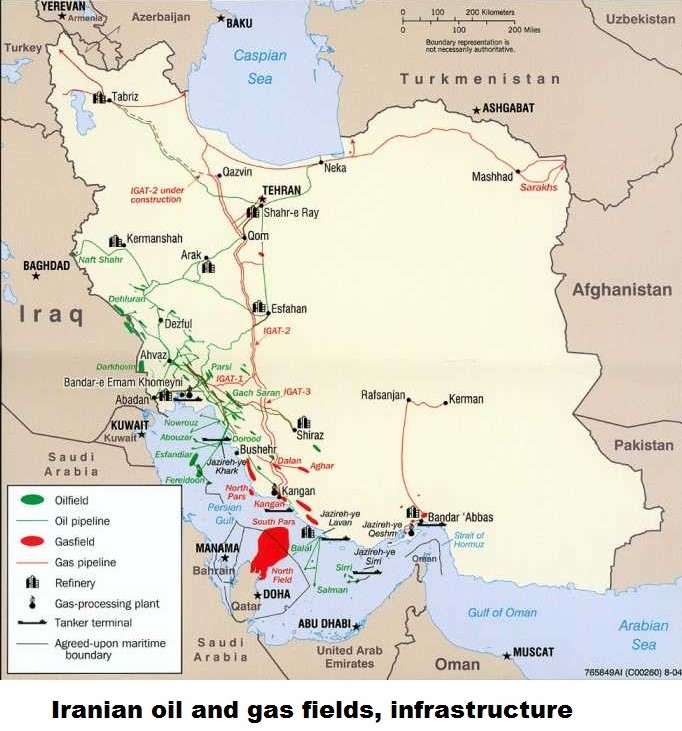

The Islamic Republic of Iran is a country built on oil. Despite attempts to reduce the country’s economic reliance on the industry, oil remains Tehran’s lifeblood — supplying roughly 40 percent of the government’s revenue in 2015 — as well as its largest export.

Even so, oil production in the country has never returned to the pre-revolution levels of the 1970s. Since then, Iran has sought to balance its revolutionary ideals with the pragmatic understanding that it needs foreign investment and technology to develop its oil sector and, in turn, to finance its government.

Pragmatism notwithstanding, several restrictions, including a ban on foreign ownership of oil reserves, have deterred foreign partners, who may be difficult to lure back. Like Rouhani is now trying to do, former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani attempted to introduce liberalizing reforms to rebuild Iran’s economy following the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s.

At the time, Iran’s political system was much different from what it is today. Foreign investment into the country’s hydrocarbon sector was anathema to many politicians, who showed little interest in attracting foreign investors, and Iran became embroiled in a bitter ideological war between its more isolationist Islamic left and a more capitalist conservative clerical base.

This dispute raged on until the mid-1990s, yielding very strict foreign investment terms. Under the terms, Iran offered contracts, whereby international oil companies would develop a field that, once completed, would be sold to Iran for a fixed fee.

Because payments were not based on production volume or price, international oil companies had no incentive to exceed production targets. Furthermore, given their high risk and limited scope, the contracts were poorly suited to maintaining aging fields or developing complex fields, projects for which Iran most needed foreign technology. Even from Tehran’s perspective, the model made it difficult to ensure optimal and continued production. But it was the best Iran’s political system would allow for at the time.

A New Political Landscape

Since then, however, Iran’s socialist and isolationist left has all but disappeared from the political scene, leaving in its place reformists who support re-engagement abroad. In fact, a broad consensus has been reached in Iran in favour of reviving economic ties with the outside world.

Iran’s new investment terms, though not yet final, differ fundamentally from their forerunners and represent a significant evolution in the way in which Tehran interacts with foreign companies. According to the new terms, international oil companies (IOCs) may enter joint ventures with Iran to work on projects and form joint operating companies to run them.

Ownership of the reserves, the backbone of the revolution, will still be off-limits to foreign companies, but IOCs will be involved in the exploration, development and production stages for up to 25 years. Iran has promised, moreover, to enter long-term supply agreements with IOCs, which Iran hopes will be able to disclose to their shareholders as assets.

Despite its plan to establish joint ventures and operating companies with IOCs, Iran explicitly distinguishes between joint operations and decision-making, hoping not to replicate past experiences in which foreign operators — mainly BP’s predecessors — called all the shots.

It remains to be seen how attractive IOCs will find it.

But unlike in previous attempts to liberalize the oil sector, the question of reserve ownership, which is so central to Iran’s revolutionary identity, at least, is settled. Iran remains focused on ensuring that foreign powers — historically the United States and United Kingdom — do not manipulate the country’s oil sector against it.

In the pre-Mossadegh era, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. was known for calling the shots in Iran’s oil sector, turning its role in exploration into a tacit co-ownership of Iran’s most precious resource. Now, BP can never claim ownership, but, as long as it respects that boundary, its expertise is needed and welcome.

In many respects, Iran is at a critical point in its history. The revolution is nearly 40 years old, and many of the key political figures that have since shaped the country are aging. Indeed, in the next decade, Iran’s third supreme leader may come to power.

Roughly two-thirds of Iranians, meanwhile, were born after the revolution, and the country faces a 25 percent rate of youth unemployment. And although a political consensus on economic reform exists, there is no such agreement on social and cultural issues, where stark ideological differences divide Iran’s various factions.

No matter who wins its presidency next year, and no matter how many foreign companies enter its oil sector, Iran will forever safeguard its most valuable natural resource: oil. Iranians would not have it any other way. ( courtesy: Stratfor)

– Edited version of a Stratfor commentary by Energy Expert Matthew Bey

https://www.stratfor.com/weekly/irans-oil-sector-returns-form?id=be1ddd5371&uuid=a73c3eb1-7643-414b-9e7f-101406245bb1

-

CHINA DIGEST

-

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

-

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

-

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

-

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

-

-

SOUTH ASIAN DIGEST

-

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

-

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

-

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

-

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

-

Comments