Retreading Myanmar's Path to Peace

* Aung San Suu Kyi’s upcoming peace conference will lay the groundwork for Myanmar’s eventual adoption of a federal system, albeit an incomplete one contingent on sustained military support.

* Several powerful ethnic armies, particularly those controlling resource-rich territories along the Chinese border, will be loath to cede any significant power to the capital.

Political violence in Myanmar predates the country itself. On the eve of colonial Burma’s independence from the United Kingdom, a pair of hit men walked into the Rangoon Secretariat in July 1947 and gunned down what would have been the new country’s leadership, headed by national hero Gen. Aung San. Five months earlier, at a conference in the Shan town of Panglong, Aung San and leaders from several of the country’s ethnic groups had forged an agreement on a federalist structure for the new nation. The pact granted extensive autonomy to the country’s ethnic minority-dominated border regions and paved the way for a provision in the nation’s founding constitution to allow secession. But in the power vacuum that the assassinations created, the agreement fell by the wayside, and many ethnic groups took up arms against the central government. A comprehensive peace in Burma, now known as Myanmar, has been elusive ever since.

Now Aung San Suu Kyi, the de facto leader of Myanmar’s first freely elected civilian government in more than 50 years, is trying to pick up where her father left off. Next month, Suu Kyi will chair the so-called 21st Century Panglong Conference, an all-inclusive round of peace talks and political discussions aimed at making Myanmar a federal state. If Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) can build on a budding rapprochement with the still-powerful military, the nascent government will be able to lay the groundwork for a more stable system. Over the long term, however, the geopolitical forces that shape Myanmar will challenge the longevity of any power-sharing structure.

The Geopolitics of Myanmar’s Conflict

The push for a federal state has been a recurring theme throughout Myanmar’s turbulent political history. In 1961, the country again neared an agreement on federalism. A year later, Gen. Ne Win seized power and suspended the founding constitution, a move he claimed was necessary to prevent the young state from disintegrating. For most of the next five decades, the ruling military governments sought to rid the nation’s core Irrawaddy River Valley of insurgents and then to pacify the country’s far-flung ethnic regions.

Myanmar, a country split by geography and a patchwork of ethnic and religious groups, requires some degree of decentralization for successful governance. Even the generals recognized the shortcomings of their military solution, establishing over time several ethnic states with limited powers. At the same time, the very factors that demand a decentralized power structure would put any federal system at risk of degenerating into no system at all.

In other words, the military’s continual push to centralize control over the country wasn’t driven merely by a lust for power, but also a desire to keep the country from breaking apart, particularly during a Cold War environment. (The insurgency was initially launched by powerful communist forces.) To build an effective state, a government must be able to control critical functions such as military force, border defence and aspects of economic planning — limiting what powers Naypyidaw can concede to the outlying states. Had he lived to see his agreement through, even Aung San would have had to eventually reckon with these forces. His daughter’s new government is no different.

Ethnic Insurgencies Persist

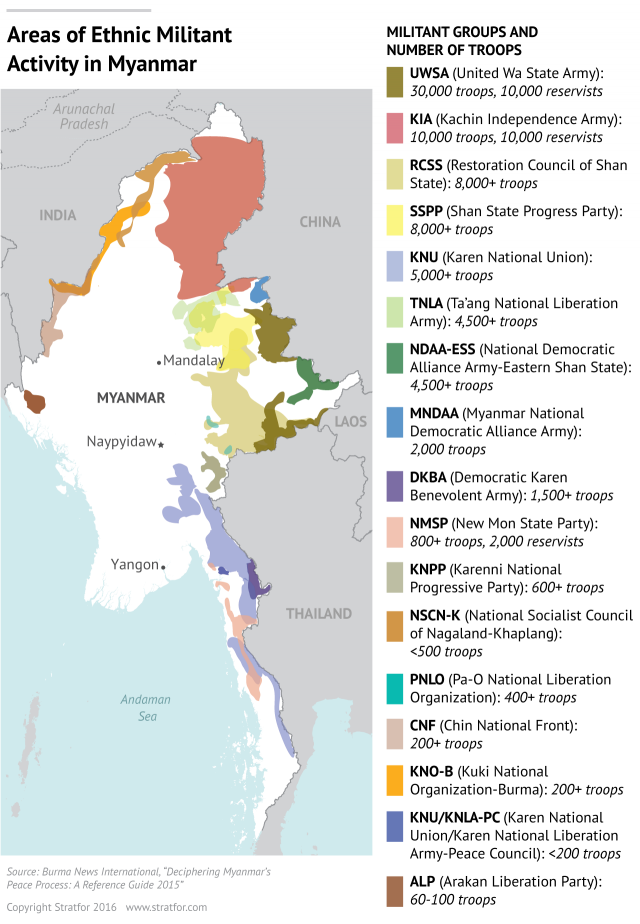

Today, Myanmar’s central government does not control most of the country’s borderlands. Instead, more than 20 armed ethnic armed groups — ranging in size from a couple hundred fighters to more than 30,000 — occupy pockets along Myanmar’s borders, some claiming huge swaths of territory. In October 2015, the outgoing military-led government signed a cease-fire with eight militant groups. But several of the strongest ethnic groups — particularly a loose network of ethnic armies with valuable holdings along the Chinese border — were banned from the discussions. Seven other groups refused to join in solidarity.

After nearly 50 years of fighting, many of the ethnic armies are well armed and adept at guerrilla warfare. What’s more, they control resource-rich, quasi-independent territories. For some, the profits of narcotics trafficking have superseded their political aims. Consequently, it is unclear what the government could offer to entice them to cede some control of their territories.

Compared with the military, though, the NLD is in a better position to rebuild trust between ethnic parties and the central government. Inevitably, politics will complicate these relationships. Since the new government took power in April, some ethnic parties have already become vocally disillusioned with its policies. Still, the advent of democracy in Myanmar, as marked by the NLD’s historic victory in November 2015, will give ethnic groups a non-violent means to address their grievances, critical to bringing a lasting end to the fighting. By inviting greater participation among Myanmar’s multifarious population, the government will empower ethnic groups’ political — rather than their paramilitary — wings. But it remains to be seen whether the holdout militias, and, more importantly, the military, will abide by a new political system.

Her Father’s Army?

Cooperation between the NLD and Myanmar’s military will be necessary to achieve any progress toward peace. Despite the NLD’s landslide victory at the polls last November, it cannot control the military, to which the constitution grants almost full autonomy over its affairs. If the military undermines the government during negotiations, the NLD will not have much recourse.

Though the military has expressed tepid support for the conference so far, several factors could obstruct negotiations. The NLD has not disclosed many details of its plan, and whatever framework it proposes is bound to include any number of sticking points. In response, the military could propose a competing federalist model — one that demands immediate militia disarmament or one designed to protect its material interests above all else — thereby derailing any progress. And because illicit border trade has long been a lucrative source of funding for the military, its role in the peace process will be all the more complicated. Furthermore, power struggles and disputes over cooperating with the NLD have put various factions in the institution at loggerheads, creating possible command-and-control problems that could further undermine a peace deal.

But over the past two months, there have been signs that the NLD and the military may be approaching a working relationship. Since last year, Suu Kyi has met with top commanders on several occasions, and the tone from both camps has become notably conciliatory. The generals are reportedly beginning to see Suu Kyi, who spent 15 years under house arrest during the previous junta, as less antagonistic than she once did and even cautiously loyal to the military, which she has famously referred to the military as her “father’s army.” Notwithstanding their differences, the military stands to gain from reconciliation with the new government. Suu Kyi’s sweeping popularity in Myanmar could help in its quest to stay politically relevant in a rapidly changing country. Moreover, Suu Kyi and the NLD hold the keys to further relief from Western sanctions and greater exchanges with Western militaries.

Prospects for Peace

Given their history and the high likelihood that their interests will eventually clash, cooperation between Myanmar’s new government and its military on the peace process is by no means assured. Conflicting reports have already emerged about whether Suu Kyi has conceded to the military’s demand that cease-fire holdouts lay down their arms before coming to the table.

Regardless, to realize its vision for the country, the NLD cannot allow the border insurgencies to grow unchecked. Nearly all the rebel groups have expressed interest in the Panglong conference, but the NLD is under no illusions that all will be ready to compromise. Militias with easy access to arms, supplies and markets in China, such as the United Wa State Army, a former ally of Burma’s Communist Party, will be especially recalcitrant. This will drive the NLD to adopt the military’s approach to the holdouts, isolating some armies and turning the others against them.

Meanwhile, cozier NLD-military relations will create other problems. Even as they ran their own candidates in the 2015 elections, several ethnic parties tacitly supported the NLD, the party best poised to end the military’s reign. Now that the NLD holds a super majority and does not need coalition partners, ethnic parties have been sidelined once again. A lasting reconciliation between the new government and the military would affirm Burman dominance in the country, leaving the ethnic parties little room to gain political ground.

The question, then, will be whether Suu Kyi’s vision of federalism — combined with the investment and development aid that is expected to ensue — sufficiently mitigates ethnic fears of a unified Burman core, while also satisfying the demands of enough militant groups to isolate the holdout rebel armies and weaken their control of the Chinese border. Even if it succeeds initially, the government will need to deliver sustained prosperity to all parties involved or else it will lose its legitimacy.

All of this highlights the limits of what the Panglong conference can achieve. Dozens of obstacles to progress in the peace process remain. Even so, Myanmar has arrived at a remarkable juncture: The military solution has run its course, allowing for a moment of grand ambition.

–By Phillip Orchard, Lead Analyst, Stratfor

-

CHINA DIGEST

-

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

ChinaChina Digest

China’s PMI falls for 3rd month highlighting challenges world’s second biggest economy faces

-

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

ChinaChina Digest

Xi urges Chinese envoys to create ‘diplomatic iron army’

-

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

ChinaChina Digest

What China’s new defense minister tells us about Xi’s military purge

-

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

ChinaChina Digest

China removes nine PLA generals from top legislature in sign of wider purge

-

-

SOUTH ASIAN DIGEST

-

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

South Asian Digest

Kataragama Kapuwa’s arrest sparks debate of divine offerings in Sri Lanka

-

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

South Asian Digest

Nepal: Prime Minister Dahal reassures chief ministers on police adjustment, civil service law

-

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

South Asian Digest

Akhund’s visit to Islamabad may ease tensions on TTP issue

-

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

South Asian Digest

Pakistan: PTI top tier jolted by rejections ahead of polls

-

Comments